Creating

Value.

Co-creators who shape their visions and transform them into value.

Vol.3

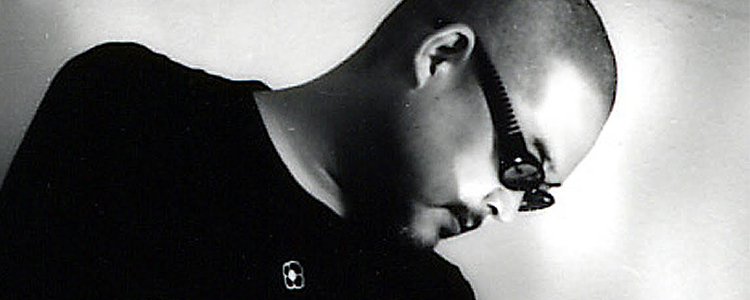

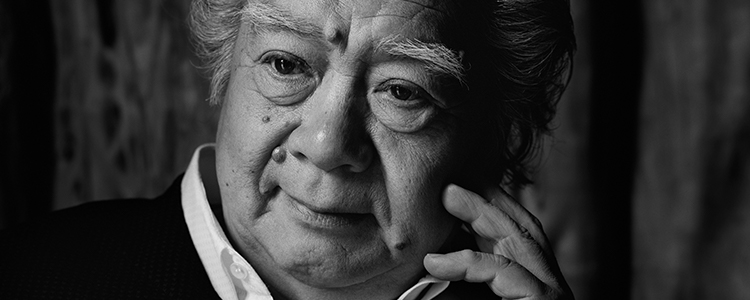

Yuuji Suzuki

Director and Partner, studio on site

Registered Landscape Architect,

First-Class Architect, Nature Restoration Promoter,

First-Class Landscape Gardening Work Operation and Management Engineer

Tokyo Denki University part-time lecturer

I want to create spaces that remain in visitors' memories, like an archetypical landscape.

Studio on site was established by a team of four landscape architects. While landscape design is not a familiar concept to most people, it embodies a world where designs are on scales even larger than architecture and which connect people with nature. We asked Yuuji Suzuki, one of the partners who co-founded studio on site, about the perspectives he believes in.

From civic engineering to sustainability, landscape design has it all.

Studio on site was founded in 1998 by myself and three colleagues from a previous job: Hiroki Hasegawa, Chisa Toda, and Toru Mitani. The concept of landscape architecture originated in the United States. The culture that developed there had to do with executing urban planning in places which would revert to desert if left alone, and creating an environment where nature and city could co-exist and people could stay comfortably and sustainably.

The concept of landscape architecture was advocated by Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of New York City’s Central Park. In the 1980s, the only place where you could study landscape architecture was the USA, so my partners Hasegawa and Mitani were educated and trained there. Landscape architecture is a broad-ranging concept which encompasses not only garden landscaping and design but also ecology and nature, as well as considerations for civil engineering and sustainability in urban planning. That’s why the first phase of many American projects is to assess the landscaping; this takes place before the architecture and involves how to position and plan the building(s) within a large plot of land. There is an established culture of collaboration and discussion between the landscape architects and the building architects, who jointly proceed with the planning process while envisioning the space. At the time we established our studio, there were not many offices in Japan which operated under this American style of thinking. The “external element” (landscape) was considered as being separate from the architecture. That’s why our studio is rooted in the desire to work together with architects in a designing process that intertwines the inner and outer elements.

The notion of landscape is very indistinct. A hundred landscape architects will give you 100 different answers and designs. Every project takes place in a different location with a different program. We seek the optimal solution and take on new challenges with each project. Call us easily bored, but we never want to do the same thing twice, ever. This was also true when we took on the landscaping for Hoshinoya Kyoto, where we made an interesting discovery. In places where traditional techniques have set down deep roots, there is no way we can ever measure up, because no proposal we could ever make would carry any weight. So then we thought, well, if that was the case, then maybe we could generate something new by collaborating with traditional craftspeople, fusing our performance. And we found that “creating” something new out of scratch wasn’t the only way to approach things.

Although we survey and analyze the land and climate before planning, these investigations do not necessarily lead directly to the design. What’s important is to visit the site, sense the elements which will affect the design, and generate ideas around the relevant factors. We place great emphasis on these gut feelings and processes. This makes overseas projects especially challenging. For instance, with Hoshinoya Bali, we had no feel for the land nor any expertise on Bali culture, so we bought and read a lot of thick books on Bali and toured the local area to get a feel for the kind of lives the local people led, the customs they had, and the culture they were fostering there, before we went to the site. Everyone on our team worked together, discussing and proposing what we were going to do. If you want to design the landscape, you absolutely have to have an understanding of the place and the things that are rooted there.

Allowing the natural and artificial to enhance each other to create a place for humans to belong.

One of the aspects of landscaping is the involvement of natural materials in the planning process, and people tend to see us in contrast with building architecture: buildings are designed with “hard” artificial materials, while landscapes handle “soft” elements like plants. But landscaping also deals with lots of manufactured and structured articles. Our design process combines these “hard” and “soft” components, not so much so that one highlights the other but so that they both enhance each other. One thing we emphasize in landscape design is to make lots of nooks and crannies; places on a human scale that make people feel comfortable hanging around in. During our planning, we’re always imagining how the places will generate traffic and how to arrange things so that people will behave in certain ways. It’s not about making a garden for people to look at: ours is a strong feeling of creating places for people to belong.

In terms of whether our work is more toward the public or the private, we can say that building architecture is more on the private side, with names to designate the function of each room or space. By contrast, landscaping is more public. Our spaces have no names, and people are free to do whatever they choose. We don’t make the rules. If the people who use our spaces give them names, that’s fine. What most fascinates me is how to create environments that people naturally gravitate toward; spaces which somehow invite people to come together and stay. For example, if we’re providing seating, we’ll try and figure out how high they should be for people to want to sit on them, through a thorough process of repeated discussions and studying with models and mockups. Our designs may seem like they’re on a grand scale, but actually, our work also involves drawing fine-tuned, centimeter-scale plans to work out all the details. Even so, there are times when we’ll visit the place after it’s completed and find that it’s being used in ways we never imagined. And I enjoy that. Whenever I come across an unusual manner of use, I whip out my camera (laughs).

Compared to the existing natural environment, our creations are small. But the best way is to edit a given site to minimize destruction to its current state. Those of us who have the privilege of utilizing the natural environment in our work must never lose respect for nature. For example, if a plan calls for cutting down trees to build a building, we may argue to move or reconfigure the building so as to leave the trees as they are.

In another one of our collaborations with Hoshino Resorts, called Harunire Terrace, there were trees in the area that were 20 to 30 meters tall. You can’t plant new trees that big even if you wanted to, so we cleverly arranged the buildings and spaces around the existing trees, so that people could hang around or sit down and enjoy looking at them. Most of the trees in the area were Harunire (Japanese elm), a rather obscure variety; nevertheless, Mr. Hoshino valued their charm as worthy of our respect, and the place was named Harunire Terrace.

Consideration for the time axis is another important factor in landscaping. For new projects, it is costly to plant large trees from the outset, and since large trees are, in human terms, aged, they don’t grow much after planting. If you plant small trees such as seedlings, they do not provide thick coverage at the start, but in 10 years, they can create a woodsy scene. These are the kinds of settings we envision for each project. Although certain projects will call for the grand vista of grown trees from the outset, we will design within the visually acceptable range and abide by the necessary conditions while we plant small trees so that they grow in appeal as time passes. Since trees are constantly growing, the landscape must look complete and perfected regardless of when it is seen. Another thing about landscapes is that they do not come to an end when they age; they are continuous. I suppose they could be called natural in a sense if we left them to their own devices, but we are careful with maintenance and management plans in order to keep them in a state that doesn’t look neglected, run-down, or unpleasant to the visitor. We consider how to incorporate sustainability concepts for skillful aging and blending with the scenery to maintain a user-friendly state.

I want to create spaces that remain in visitors’ memories, like an archetypical landscape.

Something I make a point of doing with lodging facility landscaping is to create a “draw.” Of course the actual designs and techniques will differ significantly according to the location. With Hoshinoya Bali, we planned it so that it is surrounded by terraced rice paddies farmed by the locals. Even after entering the facility premises, visitors have to go all the way around the fence, all the way to the far end of the premise before finally popping in the facility. We’re always debating where the facility should start. Should it be where the sign is? Or when visitors enter the gate? Or is it the reception counter? This will differ according to the surrounding environment and the facility, but I am always thinking about how to draw it out, how to draw people in, right up to the point where we can impress upon them dramatically that they’ve “arrived” at the facility.

Another thing I struggle with in almost every project is sequencing. This is about the strategic rolling out of scenes and situations to create a vivid impact on visitors. In that sense, the approach is critical. It’s no fun to let visitors into the entrance right away. The key is how much excitement and anticipation you can build up before you let people in. That said, you’re not trying to make a theme park. Our thinking is always rooted in how to present a sense of authenticity.

The sites we handle in landscaping are often larger than those for building architecture. Something I’m always scheming to do is to make the site feel larger than it actually is. Creating a “draw” at the approach is one tactic. Another is to enlist the help of optical illusions and perspective, like a “square” plaza that’s actually a trapezoid in shape. You can say we’re always trying, not only to draw out 100% of the potential of the site itself, but also to enhance the appeal of the land by 120%. We strive to create places amenable to diverse uses within the context of a publicly open area, so that they turn out to be comfortable spaces with an appropriate sense of distance to unify the inside and outside of the buildings.

Another major theme is the intermediate area when you delineate between the public and private domains. There are places where, even without any clear objectives or purposes set for them, there is constant origination, communication, or creative activity. While there are sure to be many different stages and phases, my aim is to sculpt our designs to match these different situations so that these places become meaningful and memorable to the visitor, somewhat like an archetypical landscape. Resorts are where experiences out of the ordinary are etched into people’s memories. How wonderful it would be if we could create places that make people look back on them and say, “If I hadn’t had that experience there, I wouldn’t be who I am now.” Nothing would make us happier than designing places that people will etch into their memories.

Profile

Born in Kamakura in 1968. In 1998, established studio on site together with Hiroki Hasegawa, Chisa Toda, and Toru Mitani. Has since executed the landscape design of many projects including university campuses, offices, resort hotels, museums, and art galleries.

- Major works

- Kashiwanoha Campus City, Tokyo Denki University Senju Campus, Okutama Forest Therapy Toke Trail Aroma Road, Mt. Fuji World Heritage Centre, and Hoshinoya Karuizawa, Kyoto, Taketomi Island, Fuji, Tokyo, and Bali.