Creating

Value.

Co-creators who shape their visions and transform them into value.

Vol.4

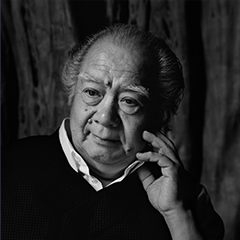

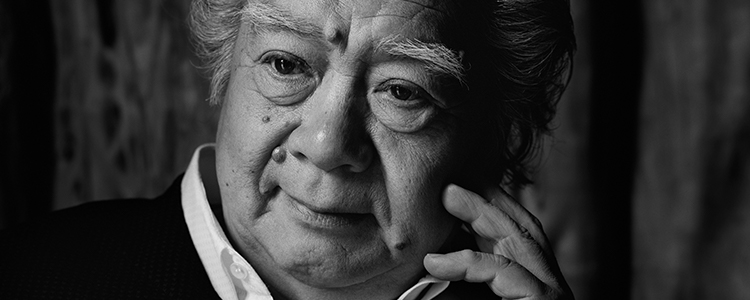

Masanobu Takeishi

President and Lighting Director,

Illumination of City Environment (ICE), Ltd.

Never sacrifice anything in the name of good design.

As the CEO of Illumination of City Environment, Masanori Takeishi has designed the lighting for a wide range of settings: commercial facilities like COREDO Muromachi, lodging facilities like Hoshinoya, and museums like Sumida Aquarium. His style is to keep in alignment with people to create highly hospitable lighting environments. We asked him about his design philosophy.

Lighting creates comfort, pleasure, and relaxation.

Lighting is designed across a wide range of domains, from landscaping to community-building, architecture, and interior spaces. Partly because I started my career in commercial spaces, my approach to light is from a people point of view. Compared to buildings and urban development plans, where you’re working on a scale of 1:100 or even 1:1000, interior spaces are on a sensory scale of 1:1. This means you take the user’s perspective, that is, you pay close attention to how people in a given space will see with your light, and how you want to shape that experience. That’s why you’ll design in different ways for different facilities and locations, approaching the task from various angles, which might include the reasons people behave a certain way there, the facility’s role, technology, hospitality, and many others. You then consider how to adjust the parameters for each of these elements to suit the facility or location.

For example, with dining facilities, fast-food places will usually be brightly lit while restaurants will be darker. This is because we expect people to stay longer in restaurants and it’s difficult to have a quiet conversation in a place so bright you can see everything around you. On the other hand, fast food places don’t want customers to hang around forever, and probably aren’t a suitable choice for people who want to take their time savoring their meal. In this case, the lighting design would consider elements like comfort, average staying time, and communication with users. For these and every other conceivable element, we adjust the parameters up and down in a process of trial and error as we explore the ideal lighting design.

Contemporary lighting design does not have much history behind it yet. However, history has seen a change in the way people think about the quality and quantity of light. Before the Industrial Revolution, people only had fire and flame to light their surroundings, so they lived in dark environments. And the Japanese were especially tolerant of, and cultivated a distinct culture around, darkness. Junichiro Tanizaki’s “In’ei Raisan (In Praise of Shadows)” illustrates the distinctly Japanese perceptions of light during the emergence of the incandescent lightbulb. What Tanizaki describes as “bright as day” was still about 2 orders of magnitude darker than modern lighting. Then, once the nation’s economic miracle was underway, productivity came to be considered a virtue, and people began to bathe their houses in bright, white, office-like lighting.

Today, people are gravitating toward the calming color of the incandescent bulb again. So our preferences for lighting quality and quantity have shifted with the various cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, but the point of origin remains the same: lighting is by nature a source of comfort, pleasure, relaxation, and contentment for us.

Never sacrifice anything for the sake of good design.

There must be no tradeoff.

The lighting for any and every space must be suited to the usage and behavior of the people who are there. How, then, should we think of design? Let me illustrate my points with some examples. Hoshinoya Karuizawa was our first assignment with Hoshino Resorts. Here, the premise was a Japanese ryokan for guests to stay overnight and spend some leisurely time, so we felt it was important to have some Japanese-style darkness. We believed that within the darkness, contemporary people would sense a calmness and culture outside of the ordinary; in other words, that dimming the lights would raise the level of the lodging facility’s hospitality. Of course, we took the highest safety precautions especially in uneven corridors, ensuring they were properly lit. Our planning was very fine-tuned and meticulous. At first, we envisioned making Hoshinoya Karuizawa like a resort in Bali – very, very dark. But then we felt that a true re-creation of that much darkness would be too dark for people in Japan, given that they had come through the economic boom. So we raised the illumination level just a bit toward the brighter end.

By our nature, humans feel relaxed and comforted when the lights are dimmed, but just because you want people to relax doesn’t mean you should merely turn down the illumination level. Darkness does not necessarily equal comfort. We have to think through everything, right down to imagining the background and lives of the users who will come into contact with that light.By our nature, humans feel relaxed and comforted when the lights are dimmed, but just because you want people to relax doesn’t mean you should merely turn down the illumination level. Darkness does not necessarily equal comfort. We have to think through everything, right down to imagining the background and lives of the users who will come into contact with that light.

We often talk about “two sides of the same coin.” I believe you should never sacrifice practicality in the name of good design, whether it be comfort, ease of maintenance, or cost of upkeep. For instance, Tsudoi no Yakata, which is the main dining hall at Hoshinoya Karuizawa, has a very high ceiling and a stepped floor design. We planned the illumination so it aligns perfectly with the overall narrative, but the challenge was to ensure a sense of privacy for diners despite the open, spacious area. So we positioned the lighting devices directly above people’s heads and made it so they could sense the blob of light. If we were to use spotlights on the ceiling to deliver light to the tables, we would need a correspondingly strong light source. But by putting the illumination above the diners’ heads, we minimize that need. We also save electricity and make it easy to change lightbulbs.

We always want to be user-friendly. But there was a problem: the light fixtures are clearly visible during the day. So we carefully arranged how they were hung from the ceiling, so as to minimize the busy, unsightly view of wires and electrical cords from the table. Our solution was to split the electrical cords down the middle so that they formed a V-shape from fixture to ceiling. This was a tricky and labor-intensive proposition, because each cord length was different and we could not make adjustments at the construction site. Even so, I think it worked nicely in the end.

It’s a balance of everything, not just design but location and temporality (time).

When we do the lighting for facilities on an ongoing basis, we are mindful of their consistent narrative and shared rhythm. The Hoshinoya resorts and the banquet room renovation for Happo-en in Shiroganedai, Tokyo are some prime examples. If a hotel or ryokan has aligned its facilities to regional characteristics, we will also factor in those traits in the lighting design.

At Hoshinoya Kyoto, we opted against using large lights to light up everything evenly. Instead, we went about positioning small, human scale lights to match how the building was originally illuminated. For instance, the lighting fixture for the sign at the entrance is covered and painted black where it’s visible to the visitor, while wickerwork at the sides allows for delicate diffusion of light. We had a company in Kyoto make this fixture for us. We also reuse lighting devices: some which were previously used in this building are now in the guestrooms.

One assignment that we really struggled with was Hoshinoya Taketomi Island, where the initial theme was “no lights.” The white sandy coral beach shines faintly at night, even without a moon. Although we could not actually eliminate all lighting, because the local venomous pit vipers like dark places (laughs), we did manage to make the surroundings dark enough so that the stone walls, called gukku, surrounding the cottages will reflect the faintest of light shone at it from far away. We avoided strong lights and blocked lights pointing upward, going for the minimum arrangement of small lights only, to enable visitors to bask in the starry skies and moonlight of Taketomi and the other Yaeyama Islands. We custom-ordered light stands for the guestrooms, so that the light would reflect on the walls and floor, spreading softly. These fixtures also incorporate the Minsa weave patterns which have their origins in Taketomi Island.

For the iconic oval pool, which is about 50 meters along its long axis, we went for the barest minimum lighting necessary. When you reduce the total quantity of light, you can begin to see the stars, even when in the pool. We used only six fixtures to illuminate the pool faintly from inside, in order to capture a beautiful sense of the atmosphere.

I have used Hoshinoya as an example to illustrate how the ideal lighting can change in response to the location or characteristic of a facility, even within a single complex. In any lodging facility, balance is important. Design encompasses more than creativity; it’s about maintaining the balance of multiple factors, including location, era, and user friendliness. Humans are constantly seeking and identifying places that feel comfortable to them, even if they are not especially conscious of doing so. Even when spending time with another person, our behavior changes in response to the other. For each facility, I intend to continue imagining how an overnight visitor might feel or act, and taking on their perspective to keep on seeking the perfect balance.

Profile

Born in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1959. Graduated from Tama Art University (Architectural Course). Worked as Chief Designer of Lighting Design at KAITO Office before establishing Illumination of City Environment (ICE), Ltd. in 1996. Handles lighting design and direction for a wide range of assignments including commercial and public spaces and facilities as well as events in Japan and abroad. Has won many international lighting contests.

- Major works

- Ao Aoyama, Tokyu Plaza Ginza (interior and common spaces), Sumida Aquarium, Hoshinoya Karuizawa